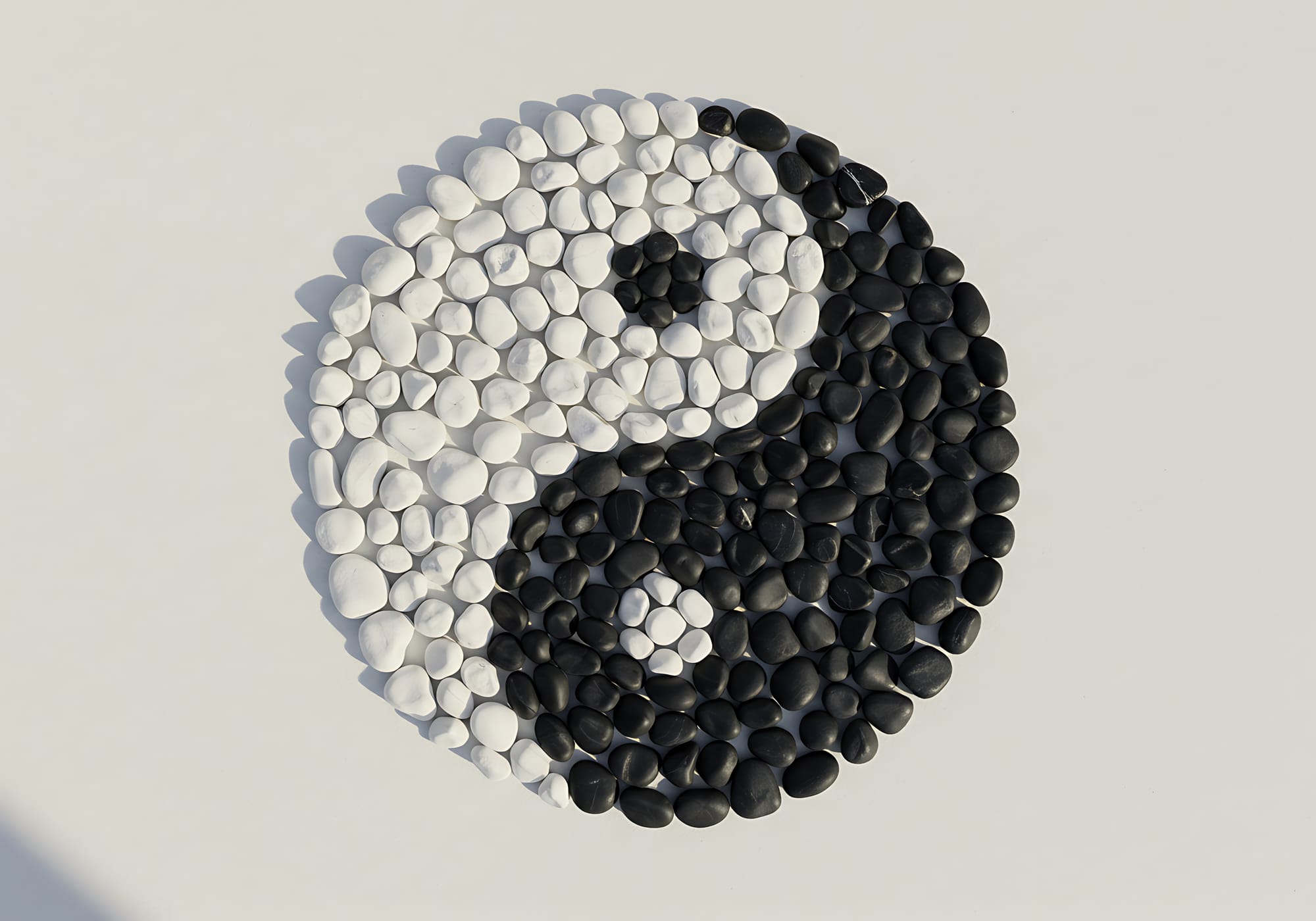

YIN & YANG — THE ARCHETYPE OF DYNAMIC BALANCE

Origins and symbolic function

Yin and Yang emerged in early Chinese thought as a way to read natural order rather than to define moral opposition. The symbol was used to describe how reality operates, from day and night to seasons, physiology, and social rhythms. The emphasis was never on separation, but on transition.

In classical sources, Yin and Yang do not exist independently. Each gains meaning only through relation, because every state carries the seed of its counterpart.

Geometry and operational logic

The Taiji diagram is not static. Its curved division shows movement rather than separation.

- The circle represents a closed totality without exclusion

- The flowing halves indicate continuous exchange

- The inner dots reveal that each condition contains the potential of the other

This geometry expresses a core principle: balance is maintained through adjustment, not fixation.

Yin and Yang as a system

Yin is often associated with stillness, darkness, receptivity, while Yang aligns with movement, light, and expression. These associations are contextual, not absolute. A force can function as Yin in one sequence and Yang in another.

Yin and Yang therefore operate as a relative system, where roles are determined by position within a cycle rather than by inherent identity.

Contemporary relevance

The Yin–Yang framework remains applicable to modern systems:

- Biological rhythms of action and rest

- Psychological cycles of outward focus and reflection

- Social dynamics between stability and innovation

- Learning processes alternating between absorption and articulation

Imbalance arises not from excess, but from interrupted flow.

What Yin and Yang ultimately describe

Yin and Yang are not ethical categories. They are an operational map. Sustainable systems depend on complementary forces and the capacity to shift fluidly between them.

Balance is not a fixed midpoint. It is the intelligence of knowing when to change phase.

☯️